STEVE LIEBER’S DILETTANTE

Dilettante 046: MADness

A ridiculously lucky thing happened recently: my wife was sorting through some old boxes of her late father’s papers when she found a small batch of his old MAD magazines from the mid 1950s— the era when it was wrapping up its time as a comic book and transitioning into the magazine it is today.

Leaving aside the thrill of learning that we own a small cache of first-rate 60-year-old comics, I was really excited to see what a typical issue of MAD, the full-color comic, had to offer. And I was not disappointed.

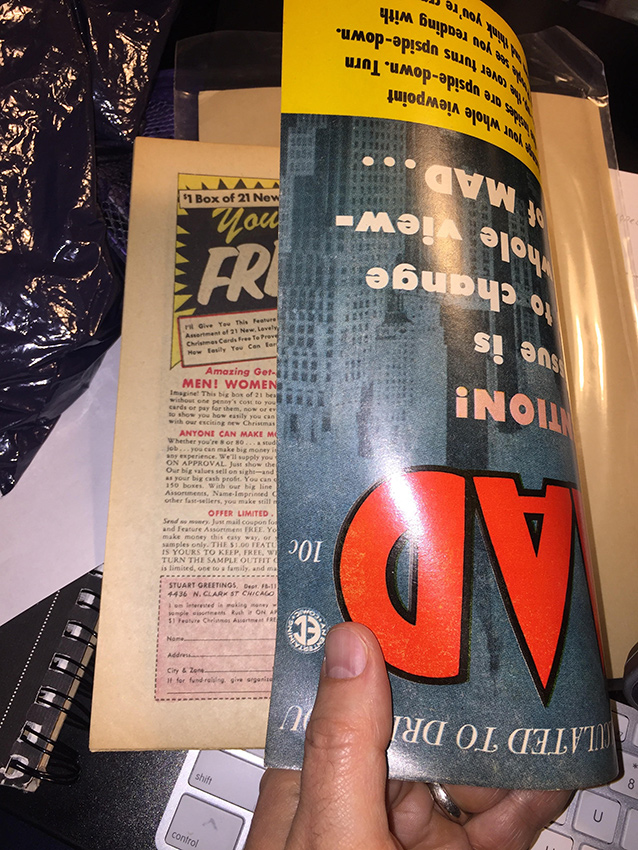

I sat down and, gingerly, gingerly, opened issue #17, the cover of which is only type, superimposed over a blue-tinted photo of skyscrapers. The copy promises that “This issue is going to change your whole viewpoint of MAD …” with a black and yellow banner across the bottom explaining that the insides are upside down. Sure enough, they intentionally attached the covers upside-down and backwards. Open the front cover and you see the last page of the comic upside-down. Even with the cover banner, I can’t imagine how many times they would have had to reassure their printer that this was what they really wanted to do.

The issue was written by Harvey Kurtzman, drawn by Bill Elder, Bernie Krigstein, Jack Davis, Basil Wolverton, and Wallace Wood, and colored (I think) by Marie Severin. As a whole it’s clearly intended to move the reader from mere diversion and entertainment to an awareness of the machinery of publishing, of culture, of politics and society. It still feels daring in 2017. I can’t imagine the impact it must have had in 1954.

Flip to the back cover, turn it upside-down and there’s your first story, a parody of George McManus’ comic strip Bringing Up Father, which was created in 1913 and already a 40-year-old institution by the time this parody was published. The strip dealt with the struggles of a newly rich man, Jiggs, henpecked by Maggie, his status-seeking wife. Initially the comic looks like any other MAD parody of the time. Artist Bill Elder draws “Jiggie and Maggs” in a pitch-perfect imitation of McManus’ elegant deco stylizations and quirky background gags. But Kurtzman foregrounds the class conflict in the strip. Their daughter is reading The Daily Worker, and Jiggie treats his employees miserably. When Maggs’ henpecking turns violent as it always does in the original strip, Elder’s line preserves McManus’ light, cartoony tone.

And then MAD pulls the rug out from under the reader. Bernard Krigstein takes over the art. Jazzy deco pen-lines become thick and brushy and fall against grimy screen-tones, communicating harsh light and murky shadows. Panel compositions shift their emphasis from flatness to depth, and the forms take on weight and heft. Jiggie explains just how painful and awful it is to live in a world of casual sadism.

The rest of the strip zings back and forth like this, one page of Elder-as-McManus, gently teasing the original strip for its tropes, followed by another of Krigstein’s ruthless, violent expressionism, in which Jiggie asks the reader to confront the violence they’ve been entertained by for decades.

And having done that, the comic goes one step further in asking how this world would really function. Jiggie snaps back at Maggs, at his daughter, at his employees, and everyone else that vexes him. The punchline is that he uses his money to hire thugs to beat the hell out of everyone and get them to do what he wants. A rich guy in a top hat might be a long-suffering victim in a comic strip, but in the real world, oligarchs get to do what they want.

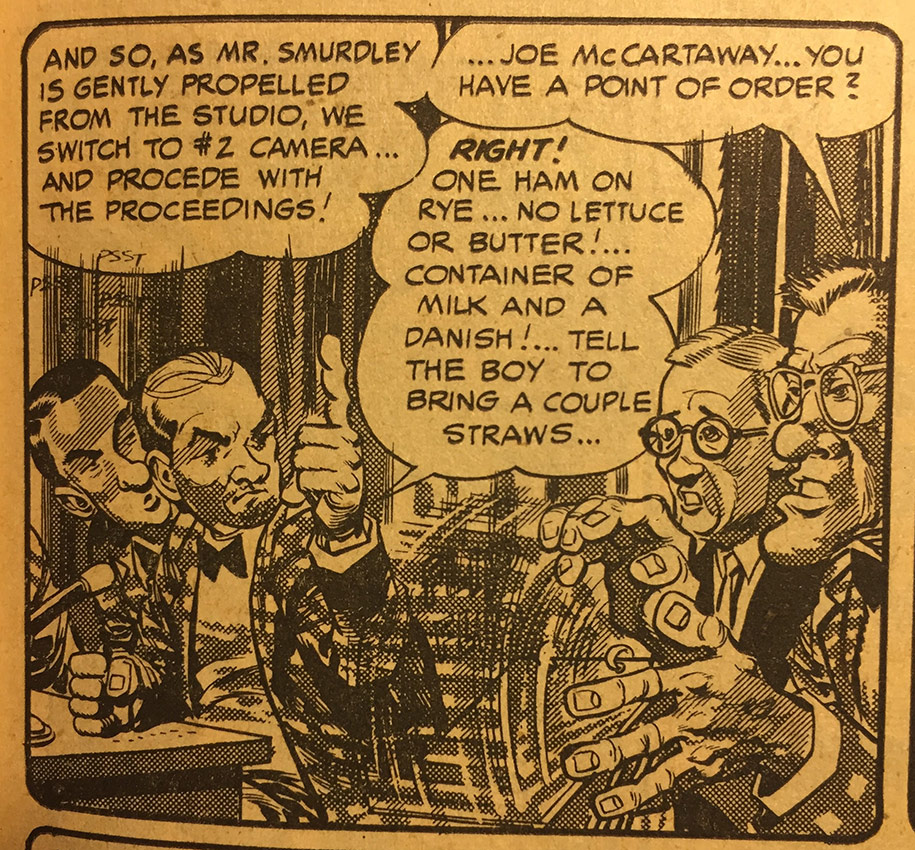

If the comic wasn’t making its point clearly enough in those first eight pages, it then moves on to a parody of the McCarthy hearings, offered up as a game show. “What’s My Shine” is drawn by Jack Davis, in black and white with craft-tint grey tones, and—rare for comics of this era—is printed without any additional color, to look more like an actual 1950s TV show. It swings directly at McCarthy’s red-baiting, and even features a creepy, muttering Roy Cohn figure virtually attached to McCarthy’s right earlobe in every panel. McCarthy’s sick lies and accusations are shown for what they really are, as is the media’s reliance on the spectacle of easy conflict.

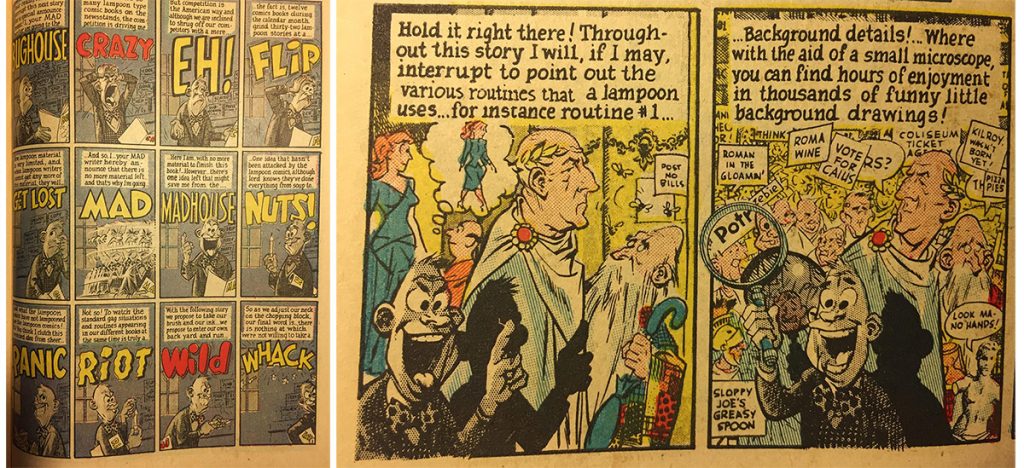

The comic moves on to satirize corporate messaging, the concept of beauty, hedonism, and finally, at the end, it satirizes the very notion of satire. A figure that represents the writer standing in front of a comics rack is at loss because there are now 12 different monthly parody comics, (there really were!) and he works the name and logo of each one into a soliloquy that runs through successive panels on a 12-panel page (above, left). This leads into a magnificent act of sawing off the limb they’re sitting on a comic called Julius Caesar, which looks like it’s going to lampoon the Marlon Brando movie of the time, but instead shines a light on all the tired tropes and strategies that go into making a lampoon. Wally Wood draws the writer standing in front of the panels of the comic, casting a shadow on them as if he was lecturing in front of a movie screen, the chaos mounts, and by the end the reader is presented with new critical tools to scrutinize the very comic he’s holding (above, right).

It’s not hard to see why authoritarians in the 1950s wanted to keep kids away from comics like MAD. This was genuinely subversive stuff, produced by the top talent of the era. I hope our comics hold up as well 60 years later.

Have you stumbled upon any treasures from the past recently? Let me know! You can reach me on Twitter @steve_lieber or on Facebook.

Steve Lieber’s Dilettante appears the second Tuesday of every month here on Toucan!