MAGGIE’S WORLD BY MAGGIE THOMPSON

Maggie’s World 084: Manners

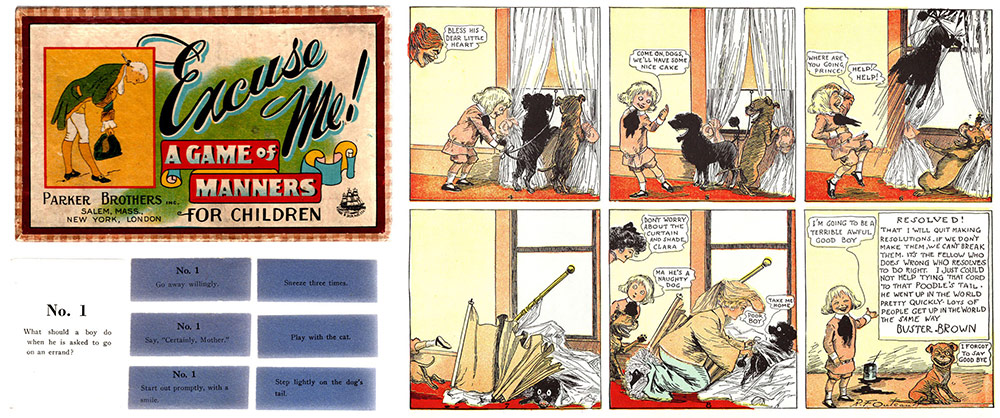

As folks mull good behavior—and possible lack thereof—in today’s society, it’s interesting to consider the history of comics “manners.” Those who are curious can begin by exploring collections of Wilhelm Busch’s Max und Moritz (1865), Richard F. Outcault’s Buster Brown (1902-1923), and A.D. Condo and J.W. Raper’s Everett True (1905-1927).

When did the topic of politeness (and, yes, lack thereof) come to comics?

August Derleth (1909-1971) was a writer, an editor, a historian, a publisher—and a comics fan. He opened his introduction to Dover’s 1974 Buster Brown: Early Strips in Full Color with this: “The ‘bad’ or mischievous boy has a long tradition in comic art and literature. Indeed, in a very real sense many early American comic strips and pages may be said to have had their inception in this tradition, which stemmed not so much from such books as Thomas Bailey Aldrich’s Story of a Bad Boy or George Peck’s Peck’s Bad Boy and His Pa as from a humorous book of maxims and pictures titled Max und Moritz, by the German artist Wilhelm Busch (1832-1908), published in German well before the turn of the century; this book served as prototype for Rudolph Dirks’s The Katzenjammer Kids (‘Katzenjammer’ is a German idiom for a hangover, but its literal meaning is ‘cats’ yowling’) and similar comics by other hands, though the verses accompanying Busch’s woodblock illustrations in Max und Moritz were sometimes rather less comic than pegs on which to hang moral lessons.” (Jeepers! Should I have also acknowledged Derleth as Master of the Run-On Sentence? Anyway, if you can find a copy of this or other such reprints, you’ll see that naughty kids should learn from the consequences of their misdeeds, even if they and the reader still find their antics funny.)

The 20th Century

Some super-polite features actually gave their names to super-politeness: F. Burr Opper’s Alphonse and Gaston (September 22, 1901-ca. 1937) took etiquette to ludicrous extremes. After you, Alphonse! No, after you, Gaston! Stephen Becker wrote in Comic Art in America (1959), “Their unbounded politesse carried them into spectacular difficulties which ordinary mortals, rude and aggressive, were spared. As they bowed and scraped, nature took its course and what might have been simple became catastrophic.”

H.T. Webster introduced Caspar Milquetoast around 1925, and the cautious adventures of “The Timid Soul” continued until 1953. Mr. Milquetoast lived in terror of offending—especially of breaking even the least restrictive of rules. In 1935, for example, he stands dutifully in front of a billboard that says, “Watch this space!” He says wistfully, “Well, really, if something doesn’t occur pretty soon I shall have to leave.”

Jimmy Hatlo’s They’ll Do It Every Time (February 5, 1929-February 3, 2008) also famously became a catchphrase, pointing out the seeming inevitability of what is said being at odds with what is done, often because of lack of courtesy.

Later

Writer and stick-figure artist Munro Leaf identified specific types of kids’ rudeness in Manners Can Be Fun (1936): “There are some people we don’t like to play with and here they are.” They’re Pigs, Whineys, Noiseys, Me Firsts, and so on. He eventually revamped the idea into a cautionary “Watchbird” feature in Ladies Home Journal starting in 1938. (As in: “This is a Watchbird watching a Whiney. This is a Watchbird watching YOU!”)

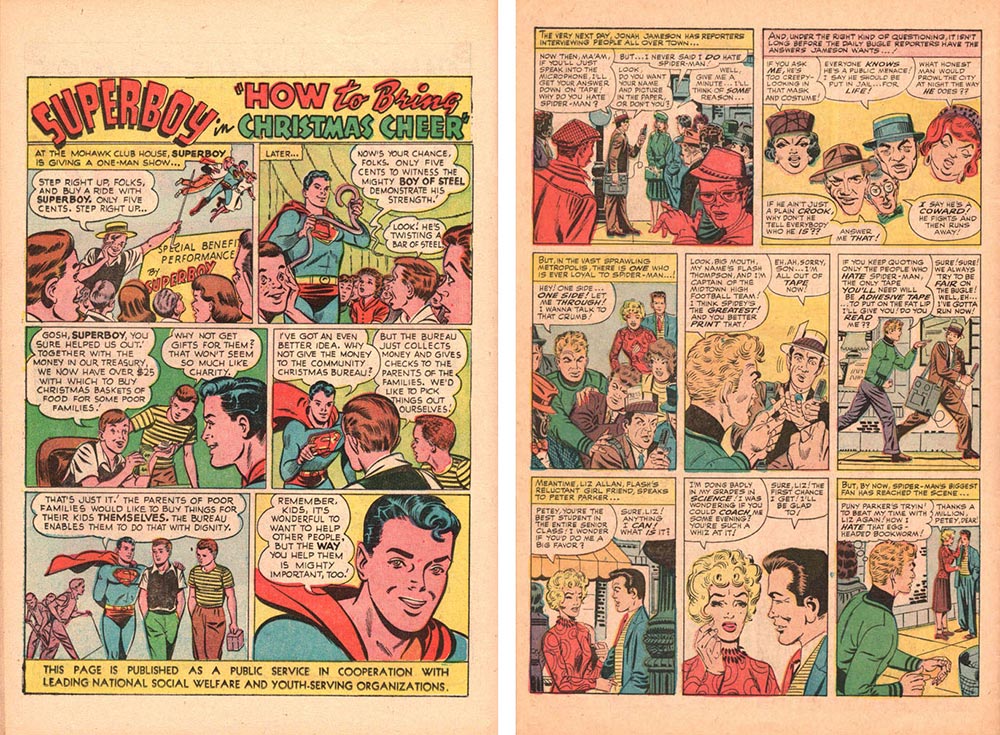

By 1940, Highlights added Goofus and Gallant. And a vast outpouring of comic-book stories featured as their basic plot device how to deal with unpleasant situations. That’s whether it’s with conflicts among Archie’s fellow teens or with super-heroes trying to deal with super-villains just being creeps. Heck, in super-hero comic books, we’re used to the ever-increasing population of outright villains, some motivated by a sort of justifiable cause, but some just plain nasty because they’re nasty. In Altman’s 1980 Popeye (largely based on E.C. Segar’s Thimble Theatre), Bluto pretty much sums it up in his “I’m Mean” song. (And there are even Golden Age ads: Why does that guy kick sand in the other guy’s face? Oh, well, Charles Atlas can help.)

Setting an Example

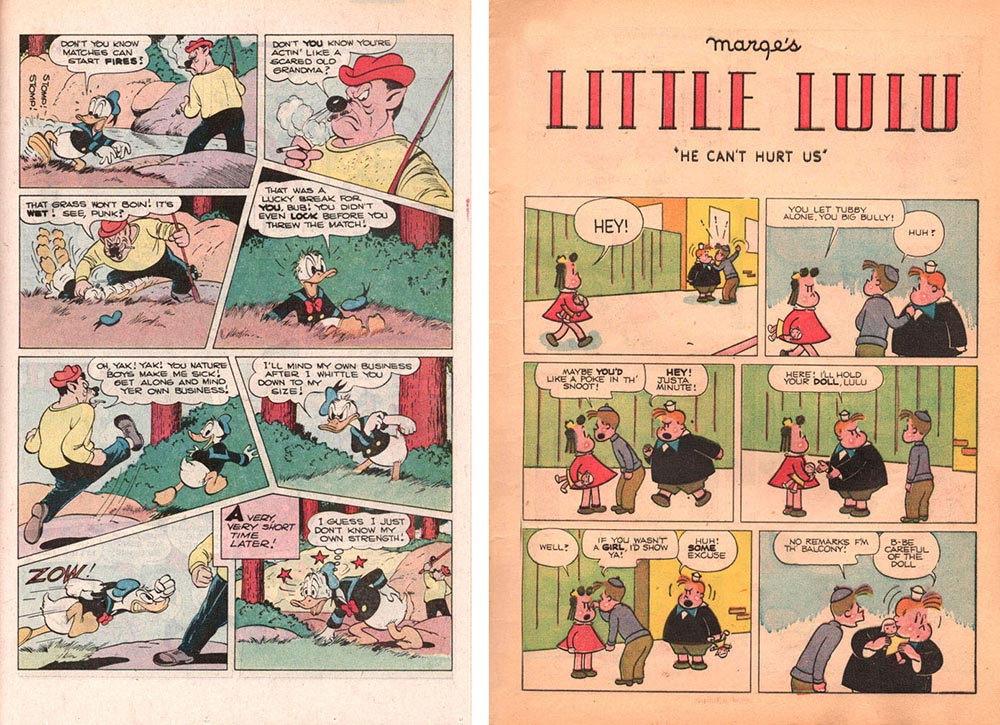

In EC’s pre-Code crime and horror comics, ghastly fates sometimes awaited jerks. In the kinder, gentler world of the Dell line, characters tended to learn proper etiquette (at least for a while) without actual destruction. Heck, Western even published Woodsy Owl and Smokey Bear comics in the 1970s.

Mind you, it should be noted that a certain amount of snark can make a character appealing all on his or her own. ACG’s Herbie Popnecker (The Fat Fury) put up with horrendous parental cruelty but, on the other hand, bopped folks with his lollipops. So turnabout, maybe? When are bad manners a proper response to bad manners?

Which is a reminder that rude characters are sometimes the ones with which readers empathize. The 1940s saw Bugs Bunny and Daffy Duck occasionally as spontaneous aggressors responding to aggression.

Cooperation

In superhero comics, we see characters coming together to solve problems by blending their talents, even when the members don’t always get along. Marvel’s All-Winners Squad was introduced in All Winners Comics #19 (1946) in a story by Bill Finger and Syd Shores. It brought together—not only the “good guys” Captain America, Bucky, Human Torch, Toro, Whizzer, and Miss America—but also the Sub-Mariner. And, speaking of Bucky and Toro, it’s not unusual for kid sidekicks to work well with heroes to do good deeds together.

That tradition includes such classic groups as DC’s (Golden Age) Justice Society of America and (Silver Age) Justice League of America. They worked in generally amiable cooperation. Such Marvel Silver Age teams as the Fantastic Four and X-Men could be a bit more conflict-laden—and it was funny. Heck, some solo characters (I’m looking at you, Deadpool) can resonate just because they’re so much fun when they’re rude.

In Any Case …

When it comes to the history of comic art itself, it has often been a highly cooperative art form. There’s a writer, an artist (maybe several: penciller, inker, letterer, colorist painter, and/or combination of all), an editor, a publisher … Well, and a printer.

The collaborations aren’t always polite, but amiable cooperation can make it work even more smoothly. Just saying. And maybe that’s another lesson in good manners.

Maggie’s World by Maggie Thompson appears the first Tuesday of each month here on Toucan!