MAGGIE’S WORLD

Maggie’s World 001: Why I Love Comics

Welcome to the first installment of “Maggie’s World,” Maggie Thompson’s monthly column here on Toucan. For this launch month, we’ve asked all of our contributors to tell us why they love comics. So without any further ado, here’s Maggie, and our first installment of “Why I Love Comics.”

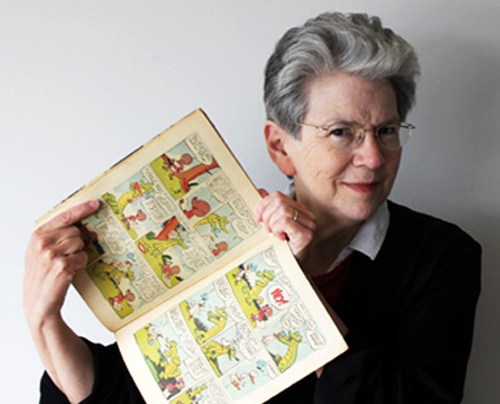

Maggie Thompson

To begin at the beginning:

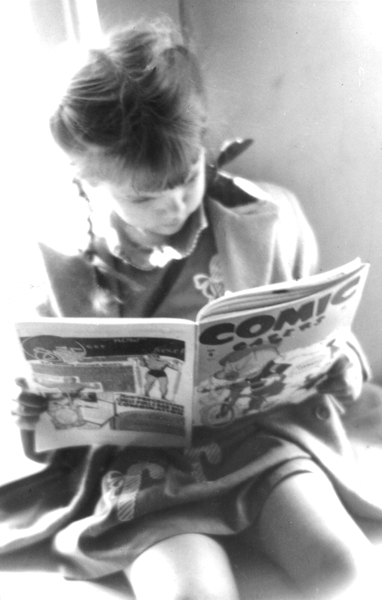

When I was 4 years old (and my mother was reading Dell’s Animal Comics to me), Albert Alligator told Pogo Possum, “Ah good at readin’ pitchers.”

That may have been my first reason for loving comics. I was good at reading pictures. In fact, I loved to read comics before I could read.

And after I learned to read—well, let me describe a portion of the first issue of something my parents published in June 1949, when I was 6 and the Golden Age of comics was morphing into attempts to deal with a changing audience, even as attacks on the artform itself were becoming ever more vitriolic and actual comic book burnings were becoming a possibility:

The Cricket, self-described as “A periodical of culture and reefinement” with the epigraph “You plays cricket, drinks tea, and lifs the pinky when you holds the cup” (a Walt Kelly quote from Animal Comics), was a fanzine published by Mom and Dad and edited by Mom “at their editorial offices, mimeograph salon, studio, dishwashing and ironing parlors, nursery and residence.” Circulation of the mimeographed newsletter (judging from the published list of recipients) was 36, but only 4 of those copies went to relatives. (It was an ongoing attempt to communicate with friends.) In the midst of a variety of book, magazine, and music recommendations, was the following essay by Mom:

Best Sellers

So many friends have asked me in grim or pathetic tones, “Do you approve of comic books?” that I feel I must make some public statement which I can hand out to such gals and run for cover while they are reading it. The question, of course, makes about as much sense as “Do you approve of books?” but it is hard to say this without being thought impertinent or irrelevant by the questioners.

Comic books are naturally appealing. Pictures, like stage drama, are more interesting than mere print. The rapid action of most of the plots and the excitement of adventure hold a child’s attention in comics as they do in western movies. Passages of slow moving description are not necessary when the action is presented in pictures.

Many objections to comic books have to do with their subject matter. It is certainly not surprising that the children of avid whodunit readers should like detective comics and that children who are offered few fairy tales should satisfy their craving for fantasy with Superman and the Green Lantern (whose doings are in their way more moral than “Big Claus and Little Claus” and most of the contents of the Red, Violet, and Blue Fairy Books). And comics are cheaper than “good” fantasy—the Oz books are still retailing at $2. I wish I could afford to supply Judy [my nickname in 1949] with books which she would enjoy more (and there are plenty) than comics.

Some mothers object that their children bury themselves in comics and no longer spend time in active “fantasy play” with their friends. Cops and robbers are supposed to have given way to afternoons in the corners of the sofa with piles of comics. Comics are also supposed to have replaced “real literature” in the lives of our young. I can see no reason why there should not be a “real literature” in comic form. It is slow in taking shape, but the work of such artists as [Morris] Gollub, [Dan] Noonan, and Kelly give promise that comics can be good reading for children. Certainly these stories have been acted out by children—I’ve seen and heard it.

Comic art is a young art. When better comics are printed, kids will read them. I have considerable faith in the taste of children—they like good fiction better than bad; but as long as they are offered only mediocre, bad, and worse, in a form that is more appealing and cheaper than good stories, they will continue to read mediocre, etc.

I don’t know how to get good comics on the market any more than I know how to encourage the writing and publishing of other good books for children—but I am hopeful that artists and publishers will come across in time for our grandchildren to have lots of fun at a very moderate cost.

The largest number of periodicals in our household seems, in spite of culture and reefinement, to be made up of comic books. Most of our collection are really intended to be comic—that is, funny. Most of them are published by the Dell Publishing Company and portray the doings of urban children (Little Lulu, Henry) or urban animal child-substitutes (Walter Lantz, Merrie Melodies, Walt Disney, Tom and Jerry, etc.). The cream of the crop were, in the recent past, Our Gang, Raggedy Ann, and Fairy Tale Parade (still Dell) with the excellent drawing, interesting stories and amusing dialogue of Walt Kelly, Dan Noonan, and Morris Gollub; but these three gentlemen seem to be deserting the comic book business and two of the publications are no longer in existence. The least painful comics still on the market other than the ones I have just mentioned seem to be the Disney ones. I should recommend a recent special, still on the stands in Canton—“Donald Duck in the Treasure of the Andes” [Dell Four Color #223, actually “Lost in the Andes” by the then-anonymous Carl Barks]—as the best of the recent dime publications for the four- to eight-year-old. We do seem to have accumulated a number of Superboy, Wonder Woman, and Bat Man opera, but these do not hold the attention of our six-year-old for more than five or six readings. Even Raggedy Ann can beat that.

So, boiled down, among more reasons I loved comics as a grade-school kid were:

- Comics tell stories quickly and clearly.

- Comics support a love of reading for entertainment, as well as education.

- Comics provide good—not just mediocre—reading for kids.

- The comics format for storytelling is more appealing and cheaper than text-only tales.

Oh, and something Mom didn’t include as a captivating aspect of comics, even for young readers, that certainly motivated me: Comics taught me the need to care for what I valued. Mind you, that has been the bane of many collectors: Thousands of comic books and comic strips create a storage crisis. On the other hand, if no one saves things, those things soon just disappear. “Oh, for heaven’s sake, Egbert, I tossed out that old copy of Love’s Labours Won because the mice had built a nest in it. The shelves look so much nicer now!” If you didn’t buy and then keep the December 1947 comic book with the story “Christmas on Bear Mountain,” you couldn’t just pick up a copy in December 1948 in order to reread the delightful tale that introduced Scrooge McDuck. It was, simply, gone. So I learned to keep what I loved.

And time went on. How perceptive of Mom in 1949! It had been only 15 years since Famous Funnies had first put monthly dime comics on newsstands—and a year since Saturday Review of Literature writer John Mason Brown had described comic books as “the marijuana of the nursery; the bane of the bassinet; the horror of the house; the curse of the kids; and a threat to the future” on a Town Meeting of the Air radio broadcast. Mom pointed out to her friends, “Comic art is a young art.” Creators were still feeling their way—even as the artform itself faced increasing attacks.

It does amuse me now to realize that Mom (with her Master’s Degree in Literature) was dodging another fact in that 1949 account of the merits of comics. She was glossing over the fact that she and Dad, then each 31 years old, also loved some of the comics that she was then discussing solely as fare for children.

It’s surely time to pause to note that this “Why I Love Comics” essay is preaching to the choir. I don’t have to assure visitors to a Comic-Con International website that comics have merit. But here’s the thing: Following the furor raised by such critics as John Mason Brown and Fredric Wertham, comics were sent back to the nursery. The Comics Magazine Association of America began to censor comics prior to publication starting in 1954. Just as comics that would engage and entertain older teens were beginning production, the field was “sanitized.” And, once again, comics were viewed by the public as kids’ stuff.

But, yes, we still loved them.

A foray today through sites on the Internet will find an assortment of discussions of the current expression “A picture is worth a thousand words.” It apparently began decades ago with a streetcar advertisement containing Chinese characters and the caption “CHINESE PROVERB One picture is worth ten thousand words.” No matter the origin, the precise wording, or the accuracy of the translation, it indicates another strength of comics: We love the powerful combination of picture and text.

A new generation of comics creators came along in the 1960s: Men and women who had grown up in a world that had, it seemed to them, always had comics. They understood the attributes of the artform and began to compose that art themselves. And comic books slowly, steadily grew up, as their creators became ever more fluent in the language of comics. Comics began to win prestigious awards outside the field, as their excellences finally became widely recognized

But now, public apprehension about comics has taken what amounts to a 180-degree turn. In early days of the medium, comics were sneered at as poor substitutes for “proper” children’s literature. Comics were burned. They were used as figurative shorthand to indicate that a character might be a few sandwiches short of a picnic. When Gomer Pyle said, “Shazam!” in the 1960s, it wasn’t to display his expertise in the popular culture of an earlier day.

These days, though, I see a different apprehension when I talk to adults about comic books—and it would be funny, if it weren’t sad. That apprehension is, simply, that comics are thought of as too intimidating to read! “What is a graphic novel?” I’ve been asked more than once, with questioners expressing embarrassment at their lack of information. At September’s Chicon 7 (the 70th World Science Fiction Convention), there was a discussion over whether the Hugo Award category for comics should be dropped, with one of the arguments being that voters weren’t qualified to vote in such a specialized field.

Heck, I’ve followed the field for more than 65 years—and I can’t keep up with the vast variety that’s out there, not to mention the ins and outs of character deaths, revamped identities, alternate universes, and retroactive continuity changes. Every year’s Eisner Awards nominees bring me many new projects I know I’ll enjoy reading. And, at last, a wide variety of comics from past eras are being newly released in reprint formats. Sometimes, sheer quantity makes being behind the curve inescapable.

But I’ve been consuming public entertainment for 65 years, and I also can’t keep up with TV shows, films, online entertainment, and new social networks. Comics are so diverse now that I can’t be aware of all of them—any more than I can be aware of every great novel being released these days. And that is simply flat-out terrific.

But let me point out one other reason why I love comics: There are thousands of fellow devotees of comics these days! People who love comics are people who read for pleasure—which makes us an elite lot. Ours is a society of literate readers who are often welcome to communicate with the very people who write and draw and edit and publish and otherwise make possible what we love. Sometimes, a few among us even provide us with events that let us meet face-to-face other people who are “good at readin’ pitchers”: comics conventions!

Maybe I love that about comics best of all.