MAGGIE’S WORLD BY MAGGIE THOMPSON

Maggie’s World 075: Dressing Up

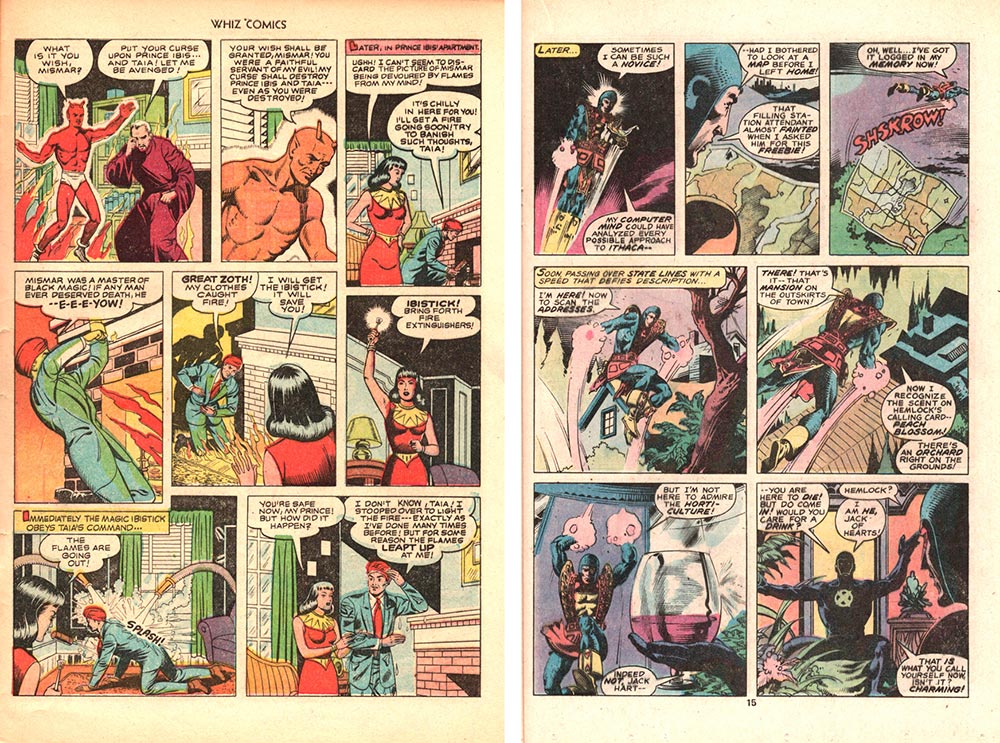

In October, variety stores fill with a wide assortment of fantastic get-ups, both for kids and for adults. But throughout the year, comics events feature a vast array of costumes on display, worn by both kids and adults.

That year-round pop culture feature is relatively recent, mind you. Though science fiction conventions included costume competitions over the decades, “hall costumes” were not the norm. Might it have been comics and similar pop culture conventions that introduced the tradition of cosplay throughout a show’s duration? (The portmanteau word “cosplay” has become the accepted term for “costume play.”)

In any case, as Batman, Spider-Man, and Wonder Woman outfits hang on store racks before Halloween, their presence sparks thoughts of comics character garb in general—including whys and hows.

Simple to Complex

In the Golden Age, crime-fighting characters didn’t have to get super-fancy. Even Denny Colt didn’t need to wear a domino mask and live in a cemetery (though that certainly set him apart); he could have just worn a business suit and snap-brim fedora most of the time.

But he was part of the whole “identity” aspect of comics adventures—a feature shared by good guys and bad—that caught the eye. It was a tradition that had existed long before comics: the idea that ordinary folks could interact with fantastic characters who were often in disguise. Such pop-culture figures as the Count of Monte Cristo (1844, Alexandre Dumas), Scarlet Pimpernel (1903, Baroness Orczy), and Zorro (1919, Johnston McCulley) expanded on the tradition, some in costume, some not.

But the whole hanging-around-in-costume gambit to beat the baddies, solve the mysteries, help the helpless, and/or save the endangered? In fact, today, we have many protectors whose clothing identifies such roles to the public: police, soldiers, and firefighters among them. What they wear lets us know the ways in which they help us.

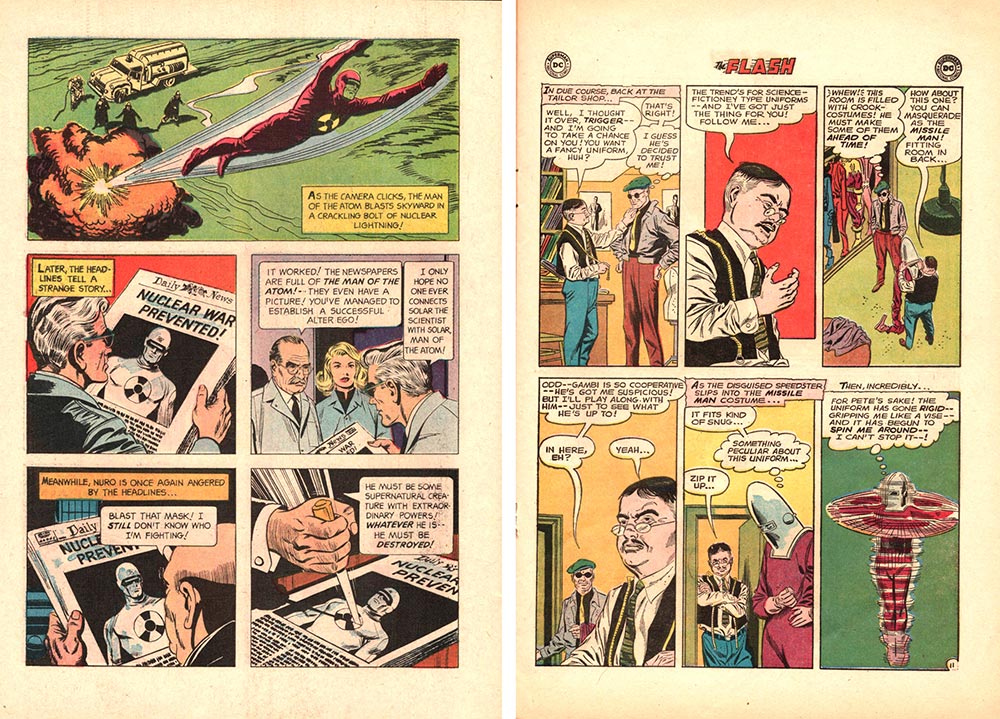

But in some fiction (see Pimpernel and Zorro), there’s an added aspect of hiding identity: High-schooler Peter Parker can fit in; crime-fighting Spider-Man stands (and swings) out.

But Also …

In addition to hiding identity, the costume can be an identity in itself.

Whether in the Golden Age, the Silver Age, or these days, when a bunch of characters are shown together (whether chatting or fighting), readers can tell, for example, Hulk from Thing and Superman from Batman.

When a story is told in pictures, costumes clarify that sort of identification. The Lone Ranger was created in 1933 for audio storytelling; when artists began to picture him, he soon donned a domino mask, but exactly what he wore varied. In the 1938 Republic serial, his mask wasn’t the simple domino known to later fans, but—what with pulps, comic strips, and comic books—his familiar mask and costume soon evolved. And then we knew who he was, whether or not he was calling his horse Silver.

Readers can spot such characters in whatever comics panels they inhabit. Heck, readers can even identify the same character as he or she exists in different eras. You know the heroes’ time period from what they wear. I have a set of three “Unemployed Philosophers Guild” licensed cups from 2015 decorated with costume evolution through the years: one each for Wonder Woman, Superman, and Batman.

Those cups reveal another aspect of costumes: Whatever the necessities of storytelling may be, costumes—and changes thereof—can also bring in licensing cash.

Again, look around stores in October. And look at the kids at your front door, as they celebrate Halloween by wearing what they’ve bought in those stores. You validate the success of their choices when you identify their super-identities because they’re wearing licensed outfits.