MAGGIE’S WORLD BY MAGGIE THOMPSON

Maggie’s World 078: 60 Years Ago

In the most recent installment of this column, I waxed nostalgic about “the Olden Days of Comic Books.”

But 1960 received only a couple of paragraphs in that look back, noting such points as, “Those who had grown up with earlier fare were now old enough to grow nostalgic for what had been, and fan communications grew stronger, as a network formed in what was then our social medium: fandom.” (Master of the run-on sentence: That’s me.)

Six Decades Ago

By summer of 1960, I was looking ahead. I was starting college at Oberlin in the fall, I was dating Don Thompson, who had just graduated from journalism school at Penn State. Given my plans, Don was going to work at The Cleveland Press, a bus trip away from Oberlin.

Both of us had been letterhacking for a number of science-fiction fanzines. Both of us had attended the World Science Fiction Convention in Detroit (Detention) the year before.

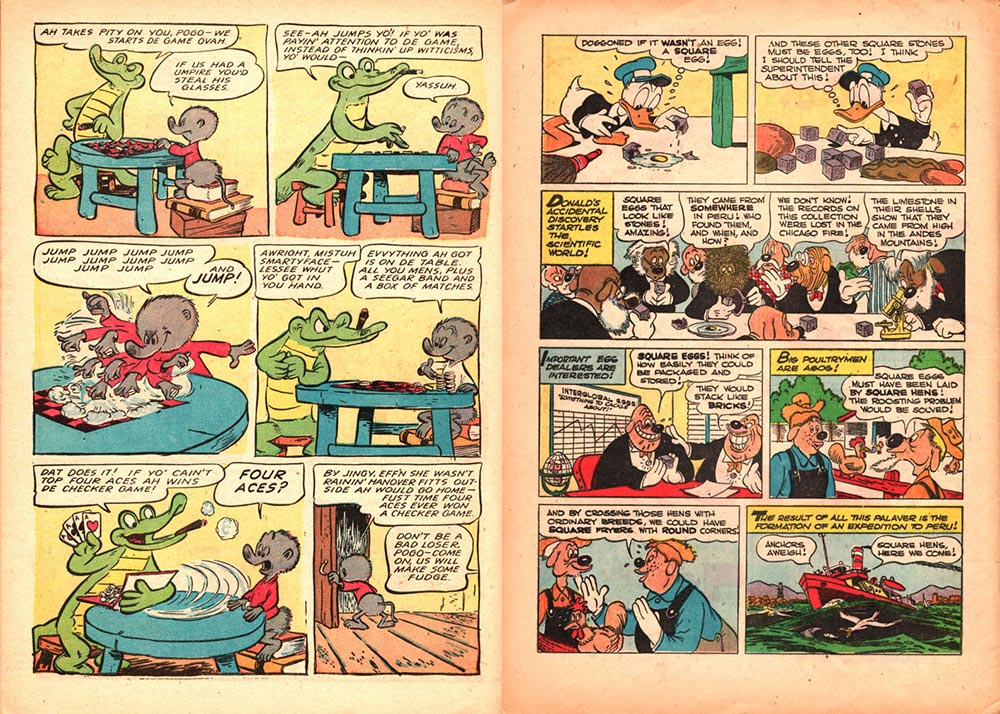

And we were both custodians of fledgling comics collections. We’d both read and kept E.C. titles. And I’d collected Walt Kelly comic books and comic strips for more than a decade. Comics had been among our conversation topics the day we met in 1957.

But among our comics challenges in 1960 was that, aside from “how to draw” guides, we could find only a few reference books in libraries:

- 1942: Comics and Their Creators: Life Stories of American Cartoonists by Martin Sheridan

- 1943: Cartoon Cavalcade edited by Thomas Craven

- 1947: The Comics by Coulton Waugh

- 1947: Secrets behind the Comics by Stan Lee

- 1954: Seduction of the Innocent by Fredric Wertham

- 1959: Comic Art in America by Stephen Becker

And not all of those were in every library. Let’s face it: Lee’s “book” had been a saddle-stitched pamphlet aimed at young readers.

Earlier Comics Groups

Comic book companies themselves had tried to create fan clubs. DC’s Superman. Fawcett’s Captain Marvel. E.C.’s Fan Addict Club. And more. Each had membership cards. Heck, a Captain Marvel club had even played a role in the 1950 Jack Carson film The Good Humor Man (with its own pop-culture connections of writers Frank Tashlin and Roy Huggins).

But the comics-associated groups had failed to morph into an ongoing comics fandom. Heck, the (science fiction) First Fandom fan David Kyle, inspired by Flash Gordon, tried his hand at a comics story in the first issue (February 1936) of his science fiction fanzine The Fantasy World. But he didn’t continue such projects, as he grew older. There were EC and satire fandoms with such “members” as Landon Chesney, Mike May, Ron Parker, Joe Pilati, Bill Spicer, Larry Stark, Bhob Stewart, and Fred von Bernewitz. But those groups had limited focuses and didn’t deal with the world of comics as a whole.

Comic Book Time

Then it was 1960, and, for some reason, 1960 seemed to be Comic Book Time.

One of the turning points may have been the appearance of Dick and Pat Lupoff as Fawcett’s Captain and Mary Marvel at the World Science Fiction Convention in 1960 (Pittcon).

But neither Jerry Bails nor Roy Thomas attended that event—although I’m guessing that it was that (and the Lupoffs’ Xero #1 with the first installment of “All in Color for a Dime”) that led Don and me to begin preparation for Comic Art #1.

My speculation at the moment? It’s that the 1959 publication of Comic Art in America led many of us to explore the art form in greater detail. Nevertheless, the question still arises: What brought together these people who felt the mutual alert of Comic Book Time? High-schoolers who wanted to make their own comics? Scholars studying popular culture even before that term was created?

While much statistical analysis of those fans remains to be done, it is intriguing to look at how old they were when they participated in the first couple years of amateur comics research.

In 1960, then: Bill Thailing was 34. Robert Coulson was 32. Ron Goulart, Juanita Coulson, Jim Harmon, and Jerry Bails were 27. Richard Lupoff and Don Thompson were 25. Larry Ivie was 24. Pat Lupoff and Bhob Stewart were 23. Ted White was 22. Roy Thomas was 20. I was 18. And Steve Stiles was 17. (I can’t find a date of birth for Hal Lynch, Bill Sarill, Mike McInerney, Jean Linard, or Dick Ellington, who were also active.)

Then …

It was a time of “Ooo, did you know about?” and “Hey, have you seen?” Don knew Will Eisner’s The Spirit. I hadn’t seen it. Information networks were established and grew. Thanks to Bill Thailing, we were able to begin collecting more. By 1976, we were able, not only to identify the identity of Carl Barks, but also to visit him and Garé.

Jerry Bails was at the forefront of a variety of comics research projects. He began by reaching out via letters columns in newsstand comic books and then establishing approaches (who’s who, amateur publishing association, awards) and supporting others (a price guide, other fanzines).

Many of us had already been keeping an eye out in used-book venues (a Salvation Army store was only a few blocks away, when we lived in Cleveland—and we had a magic moment in Kay’s Books downtown).

It really was Comic Book Time. It didn’t take long before more books were added to those earlier library collections:

- 1963: The Funnies: An American Idiom edited by David Manning White and Robert H. Abel

- 1965: The Great Comic Book Heroes by Jules Feiffer

- 1970: All in Color for a Dime edited by Dick Lupoff and Don Thompson

- 1971: Comix: A History of Comic Books in America by Les Daniels

- 1971: The Penguin Book of Comics by George Perry with Alan Aldridge

- 1973: The Comic book Book edited by Don Thompson and Dick Lupoff

And These Days …

Hey, material released in 1924 (including early installments of Harold Gray’s Little Orphan Annie) is now in public domain: which is to say that a variety of early comic art is available for reprint—although much of it still remains unvisited. But keep in mind that comic book material going into public domain in 2034 will include 1938’s Action Comics #1 [Superman] and Donald Duck. 2035 will bring us 1939’s Detective Comics #27 [Batman] and Marvel Comics #1 [Human Torch]. We’ll have to wait until 2037 for 1941’s Captain America Comics #1, Pep Comics #22 [Archie], and All-Star Comics #8 [Wonder Woman].

Then, how long will it be before English Literature textbooks will include these stories alongside the public-domain tales that appeared in my 1950s texts?

How many will have been forgotten by then? Let’s keep the classics alive for future researchers—and libraries.

Maggie’s World by Maggie Thompson appears the first Tuesday of every month here on Toucan!